I keep receiving fake news, the latest in Whatsapp. What can we do about it?

There has been a shift in journalism. Media are no longer the gatekeepers: people get and share news on Facebook and alike.

This is a good thing: it’s a democratisation of news sharing. But it doesn’t work now because people are not educated about what and how to share. They struggle to distinguish truth from falsity. As Carlota Perez would say, we have the technology, but we don’t have the institutions.

This is not strange. This is normal. You have innovation, then you set up norms that help making the best of it.

Some people suggest that these platforms should monitor false news. This is one form of governance – moving the responsibility from mass media to social media. I don’t like it, I think it is paternalistic and I certainly do not trust Facebook more than traditional media.

I think education and responsibility is more important. Journalist have ethics and principles: if people start taking over the job of journalist, they should learn from those ethics.

We need to jot down a set of principles for news sharing:

- Read the message fully and carefully. If you feel an immediate impulse to share even without reading, be even more careful: it is probably because the message is deliberately designed to push you to share.

- Verify the source of what you share. Don’t share anything that you can’t trace the origin of. Even better if you have two different sources, and perhaps reputable ones. It’s not difficult.

- Verify that the message is not already debunked as a scam. Just google it.

- Be suspicious of any message that openly ask you to disseminate it. They are most likely scams.

- Do not copy paste messages, especially if they contain first person verbs. I just received a message in different Whatsapp groups saying “I have friends in the police”. Of course I trust a message if a friend of mine says he has direct insight, but the truth is he did not have these friends, he was copy-pasting. If you copy-paste, you are directly lying to your friends.

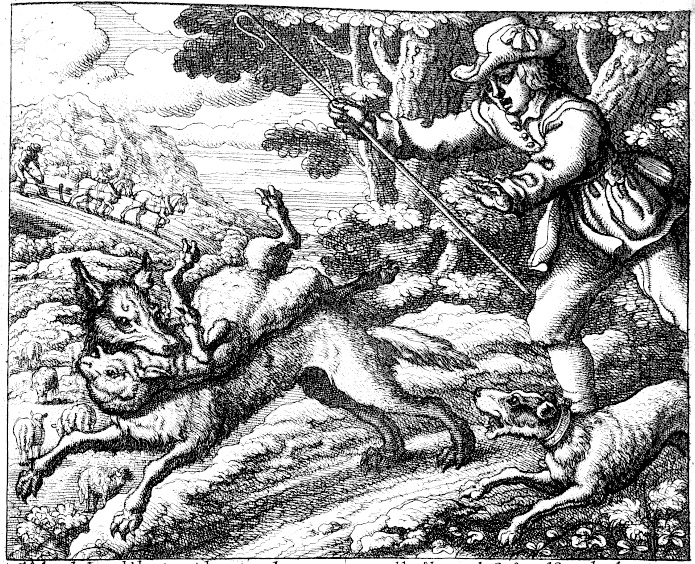

- And most of all, remember the tale of The boy who cried Wolf! If you share false news, people won’t listen to you.

What other principles can we add? And can we make a kind of self-certification for these principles to show, for instance, in our Facebook photo profile?